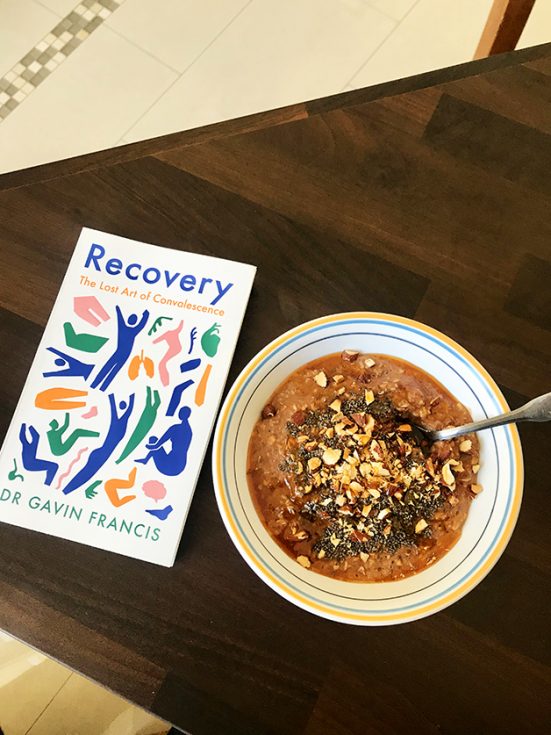

Before I boarded my flight at London Luton airport, I bought a book by Dr Gavin Francis, titled Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence. The title resonated with the words I was often hearing from my late grandfather (who himself was a medical doctor) when referring to the period of someone’s recovery from an illness. I seldom hear this expression nowadays so Dr Francis intrigued me with the title, alongside the catchy design of the book cover and its pocket-size format. It seemed like an ideal reading choice for my short flight to Vienna, to which I headed on my way back home.

Convalescence is the notion often used interchangeably with terms such as recovery, recuperation, or rehabilitation. It is broadly defined as the gradual recovery of health and strength after illness or injury. However, in our high-speed world, we’ve forgotten about the words such as ‘gradual’ or ‘slow’, even when we are ill. We expect that the period of recovery is reduced to minimum so that we can get back to our ‘normal life’, which often means checking in at work as quickly as we possibly can (because work suffers in our absence!) and resuming our usual daily routine. What we then normally want is an instant and effortless fix in the form of medication prescribed by our doctor, alongside taking heaps of supplements that we can buy over the counter. But, getting better is a process; it is a journey of recovery that requires time to rest and a mindful dedication to helping our body and mind to regenerate and return to homeostasis.

Of course, each of us will try to understand the concept of convalescence on their own terms. Dr Francis teaches us that, when we are feeling unwell, it is important to realise the signs of an underlying malaise, unhappiness, or stress in the circumstances of our life, rather than observe the symptoms as a bodily problem that needs to be fixed with medication. I here take an example of my life in London during pandemic, from which I learned a lot about myself and the system I worked and lived within. I had a job which was occupying most of my time (including free time), it required sitting at the desk for many hours (including weekends), whilst my social life was happening only sporadically, as if it didn’t matter to interact with a real human in a real, physical space. The repetition of the busy everydayness, amid the pandemic and the restrictions imposed on us, gradually replaced genuineness, community and spontaneity with loneliness, mindlessness and hyperreality. I started accumulating stress and unhappiness with life circumstances, which was creeping in and affecting me in such a way that I felt like I was slowly crumbling into pieces.

The way I felt was nothing else but burnout; the state of complete emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion. It came as a result of feeling overwhelmed with work, being emotionally and mentally drained, and unable to meet the constant demands imposed by living my isolated, yet busy, London life. I began to realise how the cult of busyness and race for productivity and competitiveness have their inherent destructive power. We often think: the more efficient, productive or organised I am as an employee, the more successful I am (the reality: the more time for working even more I create). But, I then asked myself: do achieving these results at work make me genuinely happy as a human? What is my own, intimate and deeply personal meaning of success and fulfillment? In our capitalist society, we are taught how to be maximally productive as a norm, while in the workplace we should continually justify this dreadful ‘be able to work under pressure’ recruitment requirement. But, to what end, is a question to ask.

If we decide to disagree with how things are, it can be a real challenge to unpick the inherited notions of what constitutes a ‘successful’ life. There is surely a lot we need to unlearn in order to avoid burning out, and take the actions through which we can flourish, instead of doing things that render our lives merely liveable. To flourish, we have to build in our lives many moments of rest and reflection, and create more space for idleness and creativity. Tagore suggested that in the rhythm of life, pauses there must be for the renewal of life. When we collapse, we need to rebuild ourselves as humans. It is about building a life that is satisfying, fulfilling and enjoyable; the qualities that are vital for our wellbeing.

Dr Francis mentions the Roman statesman Cicero who said that the doctors of his day often recommended a change of place for those in convalescence. There is a continuity between the body we inhabit and the environment that surrounds and sustains us. We therefore need to choose for ourselves a nurturing environment rather than the one that neglects our wellbeing. In order to make even small changes, he recommends that we should embrace the therapeutic effects of nature, try to achieve moments of grace, interact with our pets and home plants, and change the environment (travel) as often as we can. It was funny how the author mentioned an example of his ‘broken’ patient who set off travelling and found the much longed-for recuperative space in the Scottish Highlands – just like I did.

For all of us managing our way through complicated lives, Dr Francis offers hope and a rare and precious form of quiet consolation. He continually reminds us to bear in mind that all worthwhile acts of recovery have to work in concert with natural processes, not against them. This understanding of convalescence is based on the idea that each person should be able to feel in control of, and take decisions about, their own lives.

No Comments